The Land of Unequal Opportunity (Pt. 1): A History of Redlining & Its Lasting Impact on Black Homeownership

In his book, The Tipping Point, Malcom Gladwell examines how change happens incrementally, leading towards a ‘tipping point’ where all those little changes cascade into one big movement of change.

Gladwell writes about the “biography of an idea”, how it takes root and becomes a movement. According to Gladwell, transformation occurs when a particular idea gains enough social traction to — ironically, given our current predicament — spread like an epidemic.

According to Gladwell, “… the best way to understand the emergence of fashion trends, the ebb and flow of crime waves, or, for that matter, the transformation of unknown books into bestsellers, or the rise of teenage smoking, or the phenomena of word of mouth, or any number of the other mysterious changes that make everyday life is to think of them as epidemics. Ideas and products and messages and behaviors spread just like viruses do.”

Published in 2000, Gladwell’s The Tipping Point couldn’t see quite this far into the future but his sentiment stands.

2020, practically from the start, ushered in mayhem that seemed to highlight every crack in our country’s foundation; from access to healthcare to systemic racism to socioeconomic stratification, 2020 has shone a spotlight on America’s glaring flaws.

And in the wake of COVID-19, a wave of social transformation has crashed upon us with a weight that cannot be ignored. Systemic racial inequality is finally at the forefront of discussion and inaction is not an option. And George Floyd’s death was our tipping point.

As individuals, communities, and corporations alike struggle to accept their own culpability in perpetuating systemic racism at a structural level, the housing and mortgage industry must take a tough look in the mirror as we accept the part we’ve played in constructing an America that is, inherently and overwhelmingly, unequal.

If America is the land of equal opportunity, the housing and mortgage industries have played no small part in warping that idealistic vision past the point of recognition.

We are now the land of unequal opportunity, and it has been that way for a while. It’s just been too difficult for us to accept it.

The oft-repeated adage is that homeownership is the quickest tool for wealth-building, and we cannot understate how much home ownership plays a crucial role in our notions of the American Dream.

And yet 2020 in the United States reveals an America where our signature dream is largely unattainable to racial minorities because homeownership is largely unattainable for racial minorities, particularly African Americans.

It’s a tough truth to acknowledge, but it’s time to confront it instead of pretending it’s not happening.

To know where we can go, we have to look at where we’ve been. Welcome to The Land of Unequal Opportunity, our three-part series on the housing and mortgage industry’s troubling history of racial discrimination and the role we’ve played in perpetuating inequality.

It’ll be an uncomfortable ride but there’s a light at the end of the tunnel. Let’s take an uneasy walk down memory lane and then look at how we can build a brighter, more equitable future.

Redlining: a history

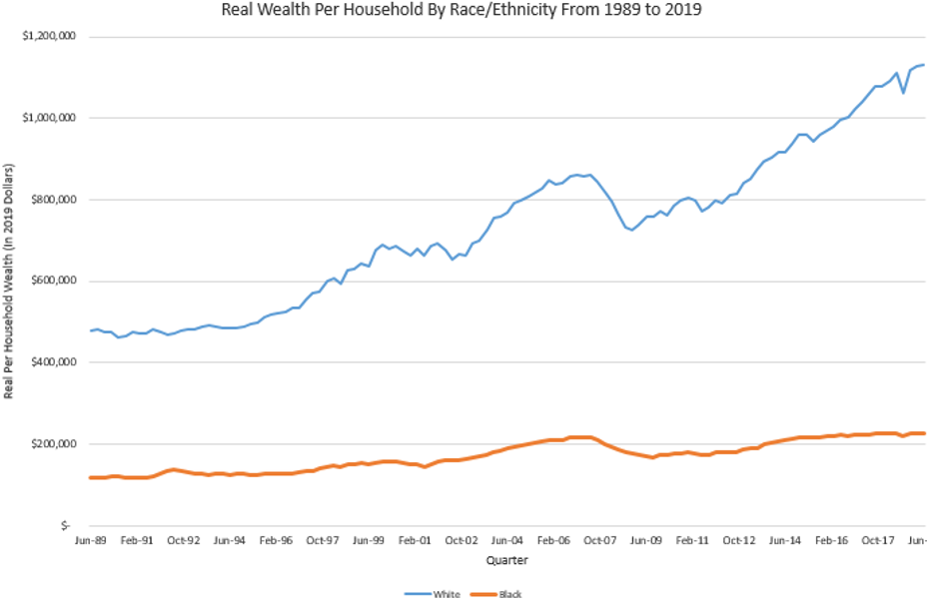

Most of you have heard of redlining; you know what it is and why it was problematic. But redlining often gets treated like a relic of a bygone era when its impact is actually still drastically felt by would-be Black homeowners. The racial wealth gap right now is wider than it was during the Jim Crow era, and unequal access to homeownership (largely due to redlining) is a huge contributor to this disparity.

As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, an African American Studies Professor at Princeton University and author of the book Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Home Ownership noted in The Guardian back in 2019:

“We have become so habituated to the ingrained treads of our racial geography that they are unremarkable. When segregation is remarked upon, it is almost always in reference to the histories of public policy and private action that were necessary to the invention of ‘black neighborhoods’ or ‘white suburbs’.”

“The much discussed wealth disparity between African American and white families is deeply rooted in black marginalization within the housing market. In the US, where homeownership makes all the difference in terms of social and class mobility, African Americans’ fraught access to this asset has put black families at a permanent disadvantage.”

And that financial disadvantage is staggering. As of 2016, the net worth of a typical white family was nearly ten times greater (at $171,000) than the typical net worth of a Black family (at $17,150).

As Ta-Nehisi’s Coates pointed out in his thorough piece for The Atlantic, “The Case for Reparations”, “Redlining destroyed the possibility of investment wherever black people lived.”

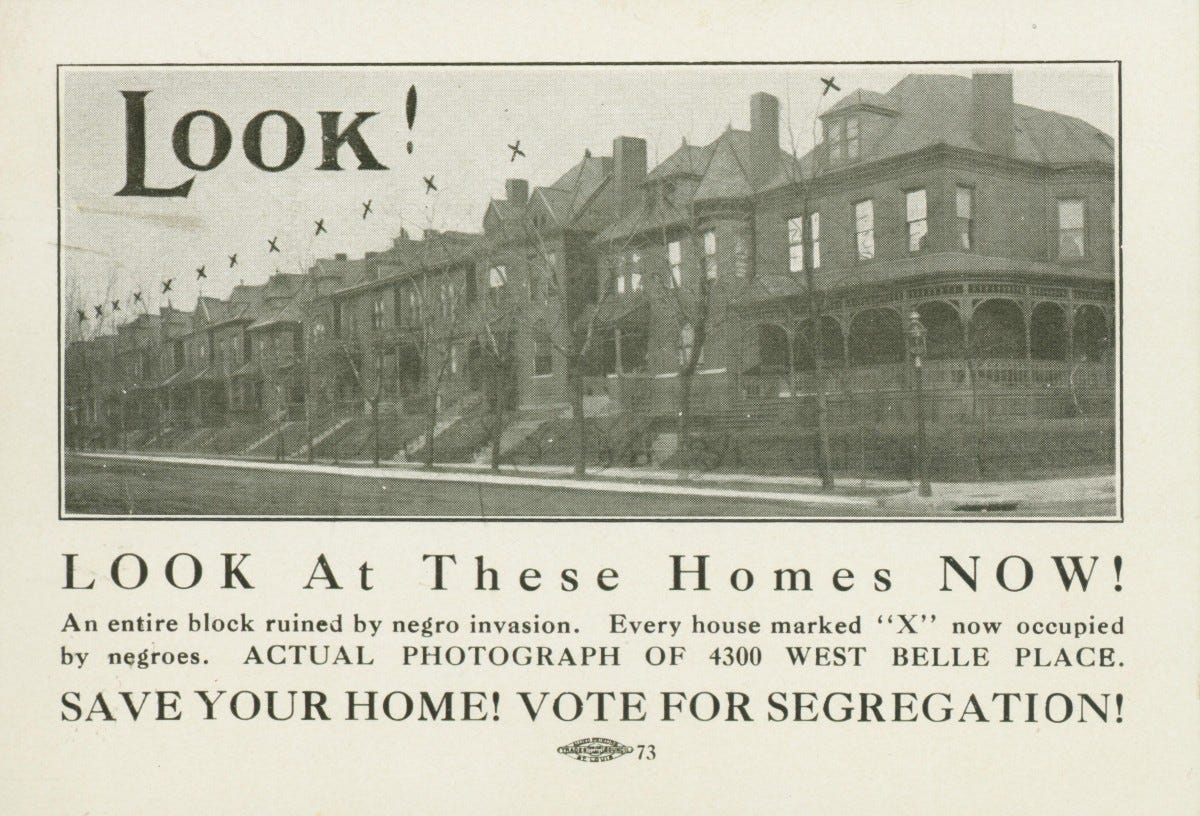

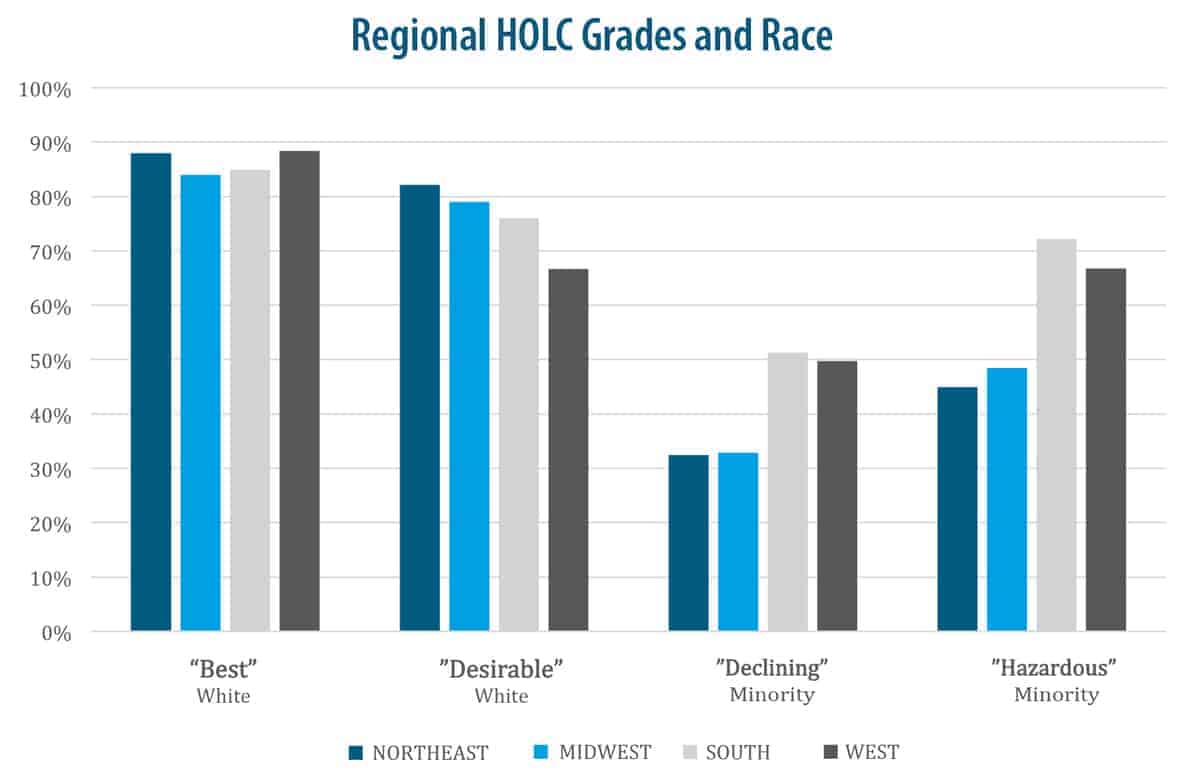

Redlining is the term given to the practices introduced by the creation of the Federal Housing Administration in 1934 that lasted until 1968. Redlining refers to the practice by which a federal agency, The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, legitimized racial discrimination by creating color-coded maps for cities across the country between 1935-1940.

These color-coded maps indicated ‘risk levels’ for long-term real estate investment and were introduced with the creation of the FHA as part of the New Deal-era legislation to lift America from the Great Depression.

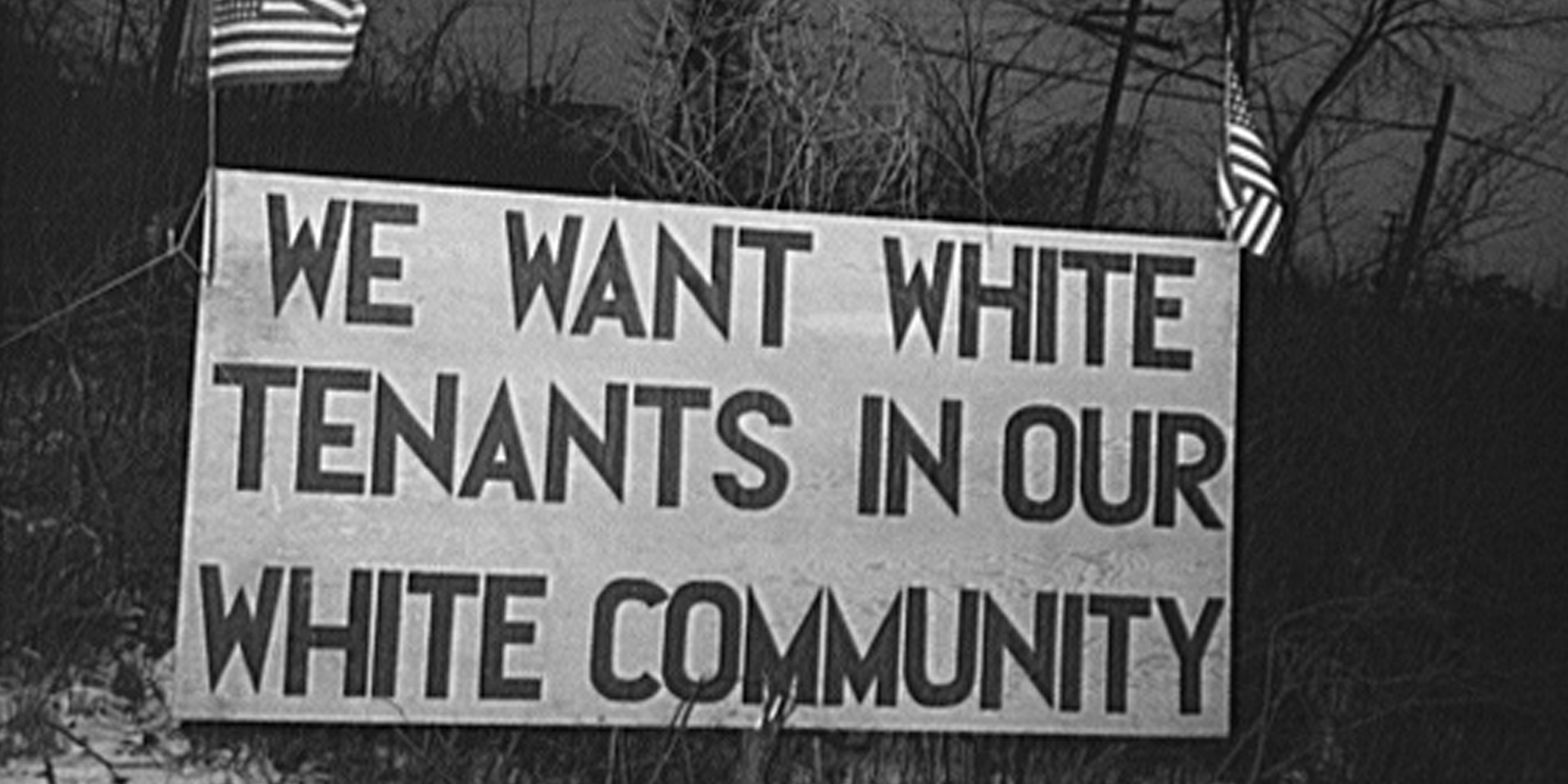

In the 1930s when redlining began, many U.S. cities were still heavily racially segregated and it was common for neighborhoods to consist predominantly of Black or white families.

These color-coded maps overwhelmingly characterized majority-black neighborhoods as the ‘riskiest’ to lend to, while predominantly white neighborhoods were green-lined and classified as safe investments.

As Alexis C. Madrigal explains in “The racist housing policy that made your neighborhood”:

“Otherwise celebrated for making homeownership accessible to white people by guaranteeing their loans, the FHA explicitly refused to back loans to black people or even other people who lived near black people.”

The key here is the ‘explicitly.’ Redlining was not accidentally racist; it was racist by design. A look at the wording of the FHA’s neighborhood classification descriptions clearly demonstrates this.

According to the FHA, an ‘A Neighborhood’, or a green-lined, low-risk neighborhood for lenders was described as follows (emphasis mine):

“Green areas are ‘hot spots’; they are not yet fully built up. In nearly all instances they are the new well planned sections of the city, and almost synonymous with the areas where good mortgage lenders with available funds are willing to make their maximum loans to be amortized over a 10-15-year period — perhaps up to 75-80% of the appraisal. They are homogenous; in demand as residential locations in ‘good time’ or ‘bad’; hence on the upgrade.”

The blue-lined B neighborhoods were also relatively low-risk for lenders, described as:

“Blue areas, as a rule, are completely developed. They are like a 1935 automobile – still good, but not what the people are buying today who can afford a new one. They are the neighborhoods where good mortgage lenders will have a tendency to hold loan commitments 10-15% under the limit.”

The riskier ‘C’ neighborhoods, which were outlined in yellow, were classified as:

“Yellow areas are characterized by age, obsolescence, and change of style; expiring restrictions or lack of them; infiltration of a lower grade population; the presence of influences which increase sales resistance such as inadequate transportation, insufficient utilities, perhaps heavy tax burdens, poor maintenance of homes, etc. ‘Jerry’ built areas are included, as well as neighborhoods lacking homogeneity. Generally, these areas have reached the transition period. Good mortgage lenders are more conservative in Yellow areas and hold loan commitments under the lending ratio for the Green and Blue areas.”

‘D’ (a.k.a. redlined) neighborhoods, meanwhile, were described as such:

“Red areas represent those neighborhoods in which the things that are now taking place in the Yellow neighborhoods have already happened. They are characterized by detrimental influences in a pronounced degree, undesirable population or infiltration of it. Low percentage of home ownership, very poor maintenance and often vandalism prevail. Unstable incomes of the people and difficult collections are usually prevalent. The areas are broader than the so-called slum districts. Some mortgage lenders may refuse to make loans in these neighborhoods and others will lend only on a conservative basis.”

These maps gave mortgage lenders carte blanche to lend predominantly to white families and prevent Black families, even those who had the financial means to buy in green-lined neighborhoods, from owning homes.

As historian Kenneth T. Jackson wrote in 1985:

“For perhaps the first time, the federal government embraced the discriminatory attitudes of the marketplace. Previously, prejudices were personalized and individualized; FHA exhorted segregation and enshrined it as public policy. Whole areas of cities were declared ineligible for loan guarantees.”

The racism behind redlining wasn’t a flaw, it was the feature.

Redlining’s enduring legacy

Redlining may have been outlawed with the Fair Housing Act of 1968, but the damage left in its wake is both enduring and significant.

Black homeowners are nearly five times more likely to own a home in a formerly redlined neighborhood than in a green-lined neighborhood, and the typical homeowner in a formerly redlined neighborhood has gained 52% less — or $212,023 less — in personal wealth generated by property value increases over the last 40 years than if they owned a home in a green-lined neighborhood.

Redfin recently released a report detailing the lasting impact of redlining on Black homeownership rates and property values, and the results are staggering.

Chicago is perhaps the most devastating case study that demonstrates redlining’s awful legacy:

“It’s a tale of two cities in Chicago,” said Redfin agent Brittani Walker. “It goes back to redlining, when Black residents lived in certain neighborhoods and white people lived in others. And the difference in home value and segregation between those places has been exacerbated by policy, education, wage inequality and so many other issues.”

She added, “I hear the systemic problems every day when I talk to clients. Home buyers have boundaries they’ve set for themselves, or a friend of a friend has set for them. They don’t want to buy in certain neighborhoods, especially on the South Side in formerly redlined areas, because those places don’t get the culture, the restaurants, the fun events — they don’t even get healthy food at grocery stores. And that contributes to why home prices don’t go up in those neighborhoods.”

Ta-Nehisi’s Coates also examines the racial segregation in Chicago in “The Case for Reparations”. Coates writes about Chicago’s North Lawndale neighborhood:

“North Lawndale is an extreme portrait of the trends that ail black Chicago. Such is the magnitude of these ailments that it can be said that blacks and whites do not inhabit the same city. The average per capita income of Chicago’s white neighborhoods is almost three times that of its black neighborhoods. When the Harvard sociologist Robert J. Sampson examined incarceration rates in Chicago in his 2012 book, Great American City, he found that a black neighborhood with one of the highest incarceration rates (West Garfield Park) had a rate more than 40 times as high as the white neighborhood with the highest rate (Clearing). ’This is a staggering differential, even for community-level comparisons,’ Sampson writes. ‘A difference of kind, not degree.’ …

“Black people with upper-middle-class incomes do not generally live in upper-middle-class neighborhoods. Sharkey’s research shows that black families making $100,000 typically live in the kinds of neighborhoods inhabited by white families making $30,000. ‘Blacks and whites inhabit such different neighborhoods,’ Sharkey writes, ’that it is not possible to compare the economic outcomes of black and white children.”

Chicago may be one of the worst examples of redlining’s legacy, but it’s not the only example. Metro cities across the country tell very similar tales.

“Redlining destroyed the possibility of investment wherever black people lived.” — Ta-Nehisi’s Coates

The homeownership gap and, indeed, the racial wealth gap writ large, is largely due to decades of redlining that suppressed Black homeownership and, by extension, prevented generations of Black Americans from achieving the social mobility enjoyed by white Americans.

In 2020, the national homeownership rate for Black families in America is 44%, while white families boast a homeownership rate of 73.7%

Homeownership is the quickest vehicle to build wealth and many of the challenges now faced by Black households are challenges that point back to this unequal access to housing.

“The expanding homeownership gap between Black and white families can in part be traced back to diminished home equity due to redlining, as it’s one major reason why black families today have less money than white families to purchase homes either as first-time or move-up homebuyers,” said Redfin chief economist Daryl Fairweather.

From stagnant wage and job growth and higher infant mortality rates to limited access to credit and higher education, the inability of Black Americans to own homes at the same rates as white Americans has had devastating, far-reaching effects that are only getting worse.

Redfin’s analysis, which covers 41 metro areas in the U.S., reveals that though redlining was outlawed half a century ago, the homeownership rate for Black families has dropped in every neighborhood over the last 40 years.

“More than half a century after it was abolished, redlining continues to dictate the racial makeup of neighborhoods, and Black families still feel the socioeconomic effects of such a racist housing policy,” said Fairweather.

“Black families who were unable to secure housing loans in the neighborhoods where they lived have missed out on one of the major ways to build wealth in this country. And even families who were able to buy homes in their neighborhood after redlining ended haven’t earned nearly as much home equity as people who bought homes in neighborhoods that were considered more valuable.”

“That has had a lingering effect on their children and grandchildren, who don’t have the same economic opportunities as their white counterparts,” Fairweather added. “Not only are black parents less likely to have the resources to pay for higher education and help with other expenses, but studies show that children of homeowners are about 7.5% more likely to become homeowners than children of renters.”

Different decade, same racist system

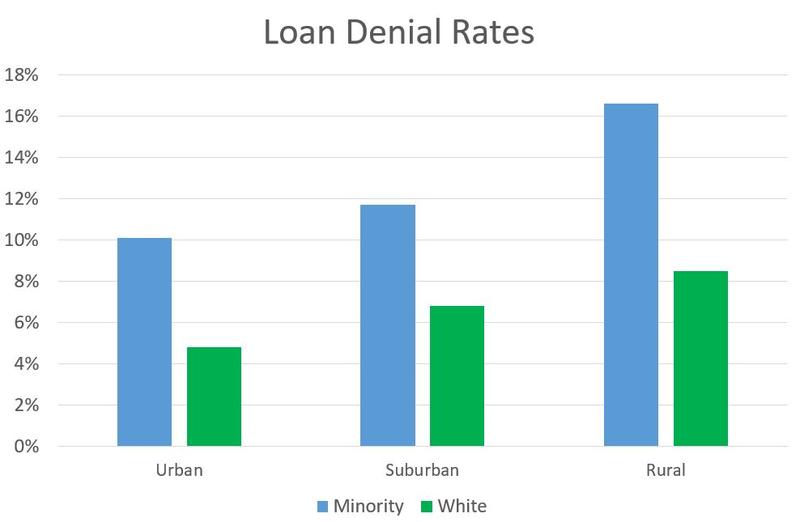

We must stop treating redlining as a historical moment because we have not put it to rest. The detrimental impact of redlining is very much alive and well today, and the mortgage market is complicit in perpetuating the discrimination that continues to impact Black Americans.

A recent study by Northwestern University reviewed all of the existing studies examining discrimination in the housing and mortgage market and found that the racial disparities in the mortgage market suggest that discrimination in loan denial and costs has not declined much over the last 30-40 years, even as discrimination in the housing market has decreased over that same period.

The Northwestern researchers found that racial gaps in loan denial in the mortgage market have declined only slightly over the past several decades, and racial gaps in mortgage cost have not declined at all, suggesting enduring and persistent racial discrimination.

“It was distressing to find no evidence of reduced discrimination in the mortgage market over the last 35 years,” said Lincoln Quillian, lead author of the study and professor of sociology in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences at Northwestern.

“Discrimination in the mortgage market makes it more difficult for minority households to build wealth through housing, contributing to racial wealth gaps. Discrimination in the housing market increases housing insecurity for minority households and contributes to persistent neighborhood segregation. These results help account for why black homeownership has not increased over the last 35 years.”

The study’s results are disheartening but not entirely surprising. Data shows that Black and Hispanic borrowers are still more likely to be rejected when they apply for a loan and are more likely to receive a high-cost mortgage.

Our racial bias, however unintentional, can even creep its way into technology built to make the home purchase process more ‘fair’.

A 2018 study out of the University of California at Berkeley found that mortgage algorithms designed to calculate interest rates perpetuate racial bias. The UC Berkely findings revealed that both online and face-to-face mortgage lenders charge higher interest rates to Black and Latino borrowers.

Black and Latino mortgage borrowers pay up to half a billion dollars more in interest every year than white borrowers with comparable credit scores.

“The mode of lending discrimination has shifted from human bias to algorithmic bias,” said study co-author Adair Morse, a finance professor at the Haas School of Business, which published the study.

“Even if the people writing the algorithms intend to create a fair system, their programming is having a disparate impact on minority borrowers — in other words, discriminating under the law.”

Equalizing the American Dream

I recently came across a quote that feels relevant here:

“If you inherit injustice, you’ve got nothing to feel guilty for. But if in the face of that injustice, you choose to do nothing, you’ve got plenty to feel guilty for.”

It’s not our fault that the system we’re a part of disproportionately hurts Black Americans. But armed with that knowledge, if we don’t work to improve our system, we’re just as culpable as our predecessors.

If you feel uncomfortable reading all of this, I get it. I’m uncomfortable writing it. I’ve cried more than once researching and writing this piece. It’s one thing to acknowledge that structural racism persists, it’s another thing entirely to look at the actual numbers outlining how deeply we have failed to uphold the values of the American Dream.

But the point of all of the think-pieces and essays you’re seeing about racism, the point of all of the recent press coverage, is to get us to stop sticking our heads in the sand.

We’ve had multiple guests on our podcast, Clear to Close, use the phrase “male, pale, and frail” to describe the mortgage industry. At the time, we laughed at the quip. But it’s not that funny, not really. It’s a call-to-action to be better.

We can’t ignore these issues any longer, and we cannot continue to pretend that the mortgage market is not directly complicit in making the problems facing Black Americans worse.

But if we want to defeat racism and build an America that is actually the land of equal opportunity that we pretend it is, we have to have these uncomfortable conversations. We have to acknowledge all of the ways that racism thrives within our socioeconomic system, within our culture, within our corporations, and within our federal government.

We need to focus less on specific actors and more on the issues that don’t implicate anyone in particular, like white privilege, implicit bias, and structural racism.

George Floyd was our tipping point as a country, and it’s on us to make sure that the social movement underway in the United States right now is our tipping point as an industry as well.

Thanks for reading Part 1 of our series, The Land of Unequal Opportunity. The point of this series is to take a frank look at racism in the housing and mortgage industry and identify steps to right those wrongs. In Part 3, we’ll discuss action items and posit ways that mortgage lenders and housing industry professionals can fight systemic racism. But before we can look at how to remedy our issues, we need one more long, uncomfortable look in the mirror. Part 2 covers the racial wealth and homeownership gaps in more detail, examining the detrimental impacts of government policy and residential segregation on Black communities along the way. Read Part 2 here.

The Land of Unequal Opportunity (Pt. 2): How Government Policy Segregated American Neighborhoods

Sources

Everyday Feminism. “4 Ways the American Dream Is Actually Just Affirmative Action for White People,” November 15, 2015. https://everydayfeminism.com/2015/11/american-dream-for-white-ppl/.

Shareable. “100 Year Timeline of Racist U.S. Housing Policy,” October 31, 2019. https://www.shareable.net/timeline-of-100-years-of-racist-housing-policy-that-created-a-separate-and-unequal-america/.

American Banker. “Bankers Need to Walk the Walk on Equality,” June 9, 2020. https://www.americanbanker.com/opinion/bankers-need-to-walk-the-walk-on-equality.

Equal Justice Initiative. “Banks Continue to Deny Home Loans to People of Color,” February 19, 2018. https://eji.org/news/banks-deny-home-loans-to-people-color/.

Bouie, Jamelle. “Opinion | The Racism Right Before Our Eyes.” The New York Times, November 22, 2019, sec. Opinion. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/22/opinion/racism-housing-jobs.html.

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. “The Case for Reparations.” The Atlantic. Accessed June 17, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/.

“Housing Discrimination in the United States.” In Wikipedia, March 16, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Housing_discrimination_in_the_United_States&oldid=945912982.

“Housing Segregation in the United States.” In Wikipedia, June 13, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Housing_segregation_in_the_United_States&oldid=962255221.

Redfin | Real Estate Tips for Home Buying, Selling & More. “How Redlining Caused a Wealth Gap and Low Homeownership for Black Families,” June 11, 2020. https://www.redfin.com/blog/redlining-real-estate-racial-wealth-gap/.

Illing, Sean. “The Sordid History of Housing Discrimination in America.” Vox, December 4, 2019. https://www.vox.com/identities/2019/12/4/20953282/racism-housing-discrimination-keeanga-yamahtta-taylor.

Jarvis, Clayton. “How Minority Homeownership Can Help in the Fight against Systemic Racism in America.” Accessed June 12, 2020. https://www.mpamag.com/news/how-minority-homeownership-can-help-in-the-fight-against-systemic-racism-in-america-224481.aspx.

Madrigal, Alexis C. “The Racist Housing Policy That Made Your Neighborhood.” The Atlantic, May 22, 2014. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/05/the-racist-housing-policy-that-made-your-neighborhood/371439/.

MARTINEZ, AARON GLANTZ and EMMANUEL. “Kept out: How Banks Block People of Color from Home Ownership.” mcall.com. Accessed June 12, 2020. https://www.mcall.com/news/pennsylvania/mc-nws-racial-discrimination-home-loans-redlining-20180214-story.html.

McCargo, Alanna, Jung Hyun Choi, and Edward Golding. “Building Black Homeownership Bridges: A Five-Point Framework for Reducing the Racial Homeownership Gap,” n.d., 15.

Nasiripour, Shahien. “Minorities More Likely To Be Denied Refinancing.” HuffPost, 12:01 500. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/minorities-more-likely-to_n_306870. HousingWire.

“[PULSE] 3 Ways to Increase and Empower Black Homeownership,” March 12, 2020. https://www.housingwire.com/articles/pulse-3-ways-to-increase-and-empower-black-homeownership/.

“Racial Discrimination in Mortgage Market Persistent over Last Four Decades.” Accessed June 15, 2020. https://news.northwestern.edu/stories/2020/01/racial-discrimination-in-mortgage-market-persistent-over-last-four-decades/.

Richardson, Brenda. “Redlining’s Legacy Of Inequality: Low Homeownership Rates, Less Equity For Black Households.” Forbes. Accessed June 12, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brendarichardson/2020/06/11/redlinings-legacy-of-inequality-low-homeownership-rates-less-equity-for-black-households/.

Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta. “Housing Market Racism Persists despite ‘Fair Housing’ Laws | Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor.” The Guardian, January 24, 2019, sec. Opinion. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jan/24/housing-market-racism-persists-despite-fair-housing-laws.

“The Atlantic Snapshot.” Accessed June 17, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/.

Thompson, Brian. “The Racial Wealth Gap: Addressing America’s Most Pressing Epidemic.” Forbes. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brianthompson1/2018/02/18/the-racial-wealth-gap-addressing-americas-most-pressing-epidemic/.

Williams, Dima. “A Look At Housing Inequality And Racism In The U.S.” Forbes. Accessed June 17, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/dimawilliams/2020/06/03/in-light-of-george-floyd-protests-a-look-at-housing-inequality/.