The 30-Year Fix (Pt. 2): Mortgage Products Around the World

Welcome to The 30-Year Fix, our three-part series on the curious case of the thirty-year fixed-rate mortgage (or TYFRM, for the sake of brevity) in America. In this series, we will cover the history of the TYFRM in America and examine why we are so uniquely reliant on it in the United States.

In Part I, we looked at the history and context of the TYFRM in America and examine why we are so fond of it in the United States.

In Part 2, we will look at mortgage products around the world and consider how and why certain mortgage products are favored in different national economies and how factors like government involvement impact mortgage product evolution.

_______

Before we jump into our world tour of mortgage products, I want to start by looking at what exactly drives mortgage product innovation.

It goes without saying that there is no perfect mortgage product. What makes a good mortgage product? Well, depends if you’re the borrower, lender, or investor, as they intrinsically have conflicting needs. Unfortunately, what makes a product more appealing to borrowers often makes it less appealing to lenders.

Features that please borrowers can be costly or difficult for lenders to provide. A borrower wants an affordable loan, the lender wants to mitigate their risk for a decent rate of return over the duration of the loan. Take, for example how an adjustable-rate mortgage with an interest rate cap reduces potential payment shock and lowers default risk for borrowers but can reduce yield for lenders.

As such, any robust mortgage market will incorporate a variety of products that balance lender and borrower priorities, with market forces largely determining the right mix without the need for much regulatory interference in determining product variations.

Competition helps drive product innovation to strike that balance, as lenders are naturally incentivized to create new products that ‘fill the gaps’ between other firms’ existing products.

This allows lenders to innovate with less pressure to compete on price, but unfortunately, these ‘niche’ products also exacerbate the information asymmetry between lenders and borrowers by introducing additional, unfamiliar products to consumers.

But how do consumer needs drive product variation and innovation? Less than you’d think, actually.

A 2018 study of the mortgage market in Australia (Mortgage Product Diversity: Responding to Consumer Demand or Protecting Lender Profit?) found that Australia’s increase in the number of mortgage products over the last decade or so has been almost exclusively driven by lenders to reduce price competition and was not significantly impacted by consumer demands, a trend that is likely applicable in other large, Western mortgage markets.

And history also matters to product innovation: a traditionally dominant product becomes familiar to both borrowers and lenders and thus can be harder to get away from.

Even so, national mortgage product preferences can shift over time. We don’t even need to look outside of our own borders for evidence of this; the popularity of the adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM) is a prime example (pun absolutely intended) of how mortgage products can phase in and out of popularity.

From 2004 to 2005, between 30 and 35 percent of mortgages in the U.S. were hybrid ARMs with short- to medium-term initial fixed rates that reverted back to variable rates at the end of a fixed-rate period. These products were designed to improve affordability relative to our trusty old FRM. The shift back towards FRMs was largely influenced by their historically low rates (driven in part by the Federal Reserve’s purchases of mortgage-backed securities), poor experiences with subprime ARMs, and trepidation about future rate increases

And finally, regulatory measures have a significant impact on mortgage product development, which we will discuss in-depth in Part 3 of this series.

The rise of a global mortgage market

Over the last several decades, we’ve witnessed the general globalization of financial markets and, with it, a liberalization in mortgage markets in many Western countries.

Much of these deregulation efforts in global mortgage markets — like easing restrictions on the use and terms of loans and allowing a wider range of financial institutions to offer mortgages — were made to foster a more efficient global system and open the market to new providers, with an eye on stimulating lender competition, thereby lowering consumer costs.

Anecdotal and statistical evidence demonstrates that housing and mortgage markets across the world are evolving in similar ways.

Many developed countries around the world have seen rapidly rising home prices, increases in mortgage debt, and worsening affordability, prompting the adoption of longer mortgage terms or interest-only payments.**

According to the International Monetary Fund, “house prices are highly synchronized across industrial countries. Specifically, a large share (about 40 percent on average) of house price movements is due to global factors, which reflect global co-movements in interest rates, economic activity, and other macroeconomic variables.”

Globalization and deregulation efforts in international mortgage markets over the last couple of decades (spurred on by waning affordability) have driven mortgage innovation at a grand scale:

“The changes that have transformed housing finance have been global in scale and are the result of global forces. These include: new technology, a societal-wide movement from government regulation to a greater market orientation, and a world-wide decline in interest rates.” — Richard K. Green and Susan M. Wachter, The Housing Finance Revolution

Though mortgage market frameworks can vastly differ from country to country, the consistency in market responses across the global mortgage market suggests that we have something to gain from looking at the commonalities and identifying where certain countries differ in product mix and design.

As house prices climb on a global scale, many national mortgage markets are using product innovation to make it easier for people to own a home. This has led to longer-term mortgage products (and other loan variants) which feature lower monthly payments.

Mortgage products around the world

The great interest-rate debate: fixed vs. adjustable rate mortgages

It should come as no surprise that one of the biggest areas of differentiation across global mortgage markets is a preference towards either fixed-rate, adjustable-rate, or hybrid mortgage products.

Australia, Spain, Ireland, Korea, and the United Kingdom are dominated by adjustable-rate mortgages (typically with a short-term initial fixed rate). Designs may vary (for example, in Australia, Ireland, and the U.K., the interest rate is set at the discretion of the lender, called a “reviewable-rate loan”, but interest rates are typically adjusted for all borrowers at the same time in these markets). Meanwhile, Canada, Spain, Korea, and the U.S. offer indexed adjustable-rate loans where rates are tied to changes in the underlying index.

Initial fixed-rate discounts for ARMs are common in Australia and the U.K., although these discounts are significantly reduced compared with those seen in the U.S. during the ARM boom, typically around 100 basis points for a duration of one or two years.

On the fixed-rate front, short- to medium-term fixed-rate mortgages are very common in a number of countries including Canada, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. These loans are typically “rollover” or “renegotiable” rate loans where the rate is fixed for a period of one to five years followed by a longer amortization period (usually 25 to 35 years).

At the point of rollover, the rate is reset to the market rate. We will delve deeper into prepayment penalties in a moment, but with these loans, there is typically a substantial prepayment penalty during the fixed-rate period in the form of a high yield maintenance penalty.

The United States is almost exclusively unique for its high proportion of long-term fixed-rate mortgages with no prepayment penalties.

France is the only other country with a large number of long-term fixed-rate mortgages.

France is the only other country with a large number of long-term fixed-rate mortgages.

However, these FRMs come with prepayment penalties (maximum three percent of the outstanding balance or three month’s interest). Germany does offer mortgages that can be fixed up to 15 years with a 30-year amortization but these loans carry a yield maintenance prepayment penalty during the fixed-rate period.

While long-term fixed-rate mortgages with a prepayment option used to be the dominant mortgage product in Denmark, their popularity has waned as low and falling short-term rates have encouraged Danish borrowers to gravitate towards medium-term rollover mortgages. In 2004, 50% of Danish mortgages were FRMs and another 20% were medium-term fixed-rate loans. By 2009, the market had shifted towards adjustable-rate and short-term fixed-rate loans, with 80% of Danish borrowers utilizing these loans.

From a macro perspective, these mortgage product trends seem to give borrowers more options and flexibility over their tenure as a homeowner. Shorter-term loan periods and hybrid loan products offer stability and risk mitigation options; in many countries, borrowers can manage their interest rate risk by taking out multiple loans on the same property, either via multiple loans with varying short- to medium-term fixed rates (Canada, Germany, Switzerland) or by fixed- and adjustable-rate loans secured by the same property (Australia, U.K.).

Prepayment penalties

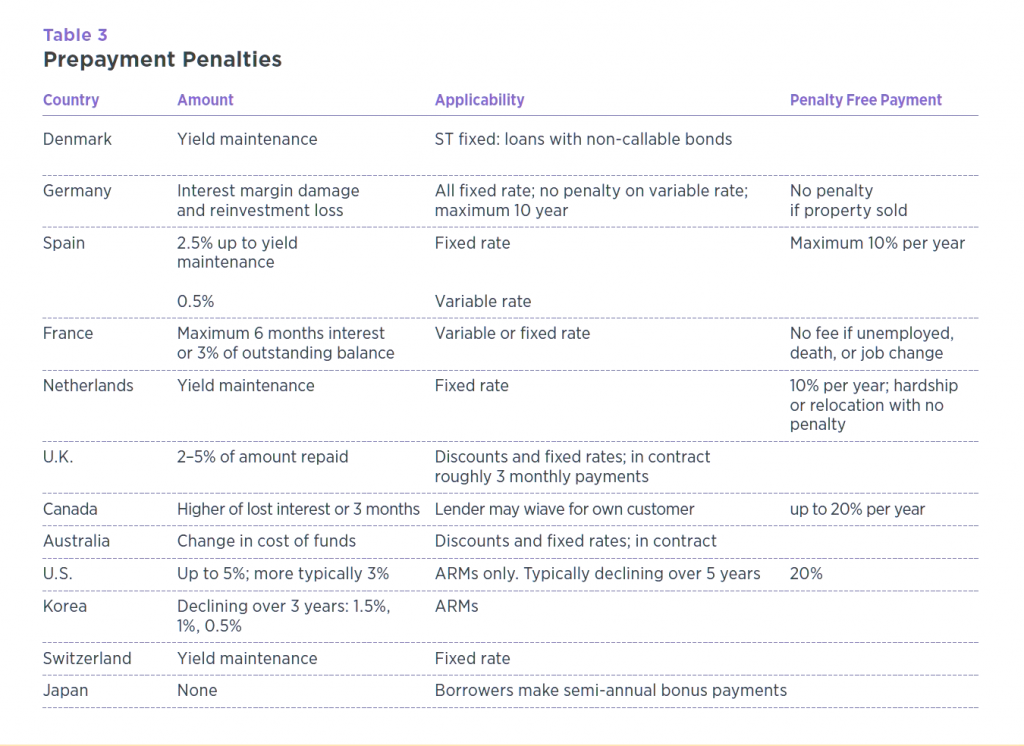

With the exception of Denmark, Japan, and the United States, fixed-rate mortgages across the globe are typically subjected to prepayment penalties.

For the sake of expedience, rather than explaining the nuances in prepayment penalties, this chart from the Research Institute for Housing America sums up how prepayment penalties vary across countries:

Government-owned or government-sponsored mortgage institutions

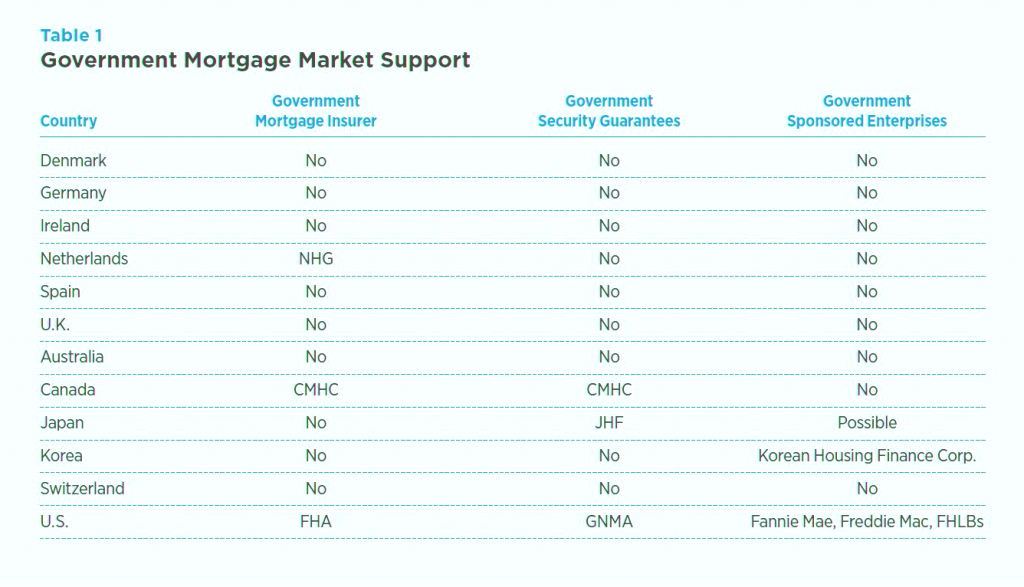

Among the countries we’ve been discussing, there are considerable differences amongst them when it comes to the presence of government-owned or government-sponsored mortgage institutions.

The U.S. is unusual in that our mortgage market uses all three types of government-supported mortgage institutions or guarantee programs: mortgage insurance, mortgage guarantees, and government-sponsored mortgage enterprises.

Other than that, government-owned or -sponsored institutions are few and far between.

Source: Research Institute for Housing America

Source: Research Institute for Housing America

Canada has government guarantee programs and government-backed mortgage insurance programs while the Netherlands only has government-backed insurance programs. Japan only offers a government guarantee. Korea, meanwhile, has a GSE modeled after the United States.

Even so, the market share of government-backed institutions in Korea, Japan, and Canada is much smaller than that of the U.S.

Amortization and term

Mortgages in most countries are annuity loans with a level payment with typical terms ranging from 20 to 40 years. A report by the European Central Bank in 2007 found the average loan term in Europe to be between 20 and 30 years.

Longer-term products are seen in some countries; terms up to 50 years are available in Spain and France, and Finland has an option for a 60-year product, though these longer-term products have a low market share.

Japan and Switzerland represent the extreme end of the spectrum, with the option of a 100-year, intergenerational mortgage product.

Interest-only loans saw a global spike in the mid-aughts, but the popularity of interest-only mortgage has fallen in the wake of the financial crisis.

“Flexible” mortgages are also common in many countries outside the U.S.; these loans allow non-constant amortization to accommodate income fluctuations like short-term unemployment or variable income. Some of these loans even allow borrowers to skip payments or take payment holidays. In Australia and the U.K. in particular, borrowers have the ability to underpay or take a payment holiday and then overpay and borrow back without the need to take out a second mortgage. The number of unpaid payments allowed per year is limited and unpaid interest is capitalized in the loan balance.

The U.K. and Australia have also witnessed the rise of a “sophisticated variant of the flexible mortgage” called the “offset mortgage” or “current account mortgage” which allows the borrower to control mortgage borrowing through a current account. Salary is deposited into the current account, lowering the outstanding balance by the salary amount. As debit charges come through the account, the balance rises. These loans offer interest savings from paying down the debt since interest is charged daily.

An offset mortgage “allows the borrower to keep balances on mortgage, savings, and current account in separate accounts but all balances are offset against each other, allowing the possibility of reducing the interest paid and the mortgage being repaid early. Offset mortgage rates can be fixed or variable and there is a maximum LTV.”

Default risk

Interestingly enough, the United States typically sees higher default and foreclosure rates than most of the countries mentioned in this piece. Of the countries we’ve discussed, only Spain and the U.K. saw a significant rise in mortgage default during the financial crisis.

Though housing markets in many of these countries are more volatile than the United States on average, the incidence of default and the prevalence of negative equity in other countries remain far below the United States. A report on global mortgage trends by Research Institute of Housing America and MBA cites mortgage product design as a chief reason for our higher default rates:

“In the United States, mortgage product design has been linked to high rates of mortgage default, though underwriting variables appear to be the dominant factor. To date, mortgage product design has not been implicated as a cause of mortgage default outside of the United States. In fact the use of ARMs has been cited as a cause in lower than expected default rates in Spain and the U.K.”

Though some of this analysis may be tied to the subprime crisis in the United States, it’s interesting to note that so many other countries with economies of scale have been able to offer a more diverse range of products without seeing a significant rise in default rates.

The U.S. mortgage market: an atypical animal

This virtual mortgage market globetrotting gives us a better idea of the big picture macroenvironment. But what have we learned from the big picture?

Most obviously, the United States mortgage market consistently differs from other developed national mortgage markets on a number of fronts, most notably in terms of mortgage product preferences and design.

We are particularly unusual in our singular preference for the long-term fixed-rate mortgage, and similarly unique for our reliance on government securitization to finance housing. In both cases, this is intrinsically tied to the presence of government-backed secondary mortgage market institutions that lower the relative price of this type of mortgage.

We are also an outlier for our bans and restrictions on prepayment penalties. American consumers pay far more in interest on long-term fixed-rate products, essentially paying an interest premium to gain the option of prepayment without penalty.

Before the financial crisis, the U.S. had one of the richest sets of mortgage product offerings among the countries we’ve discussed. The post-crisis course-correcting has led us to lean on the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage as a crutch, driven in large part by the historically low interest rates for FRMs.

We’re still recovering — financially and socioculturally — from the Great Recession, but perhaps it is finally time to confront our fixation on the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage and see it for what it is: an outdated product that we’ve relied on as a safety blanket after a period of crisis.

Or, alternatively, an overutilized mortgage product that government securitization has lured us into believing is more beneficial to borrowers and lenders than it actually is.

We can’t view the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage in a vacuum.

We need to ask ourselves how to alleviate our fixation on the long-term FRM and stimulate mortgage product innovation to achieve a more balanced, robust product mix that better speaks to borrower, lender, and investor needs.

Part of the answer lies in GSE reform to help lessen our dependence on the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage. And that part of the answer is rather complex, but we try to address it in the final installment of “The 30-Year Fix.”

**Please note that much of the information about national mortgage markets and products in this piece comes from The Research Institute of Housing in America and the Mortgage Bankers Association’s 2010 joint report, International Comparison of Mortgage Product Offerings. Wherever possible, I have tried to pull from more recent data (most notably, from a 2018 report from the European Journal of Housing Policy, Mortgage Product Innovation in Advanced Economies: More Choice, More Risk) but in some cases, the global data may reflect 2010 trends that are not as prevalent in today’s market.

<<< Read Part 1 Read Part 3 >>>

Sources

“A Timeline of Mortgage History in the United States. | Brad L’Engle.” Accessed September 23, 2019. https://www.lenglemortgageprofessionals.com/a-timeline-of-mortgage-history-in-the-united-states/.

Adams, Kristen. “Homeownership: American Dream or Illusion of Empowerment?” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, December 13, 2009. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1467896.

Almenberg, Johan, Annamaria Lusardi, Jenny Säve-Söderbergh, and Roine Vestman. “Attitudes Toward Debt and Debt Behavior.” Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, August 2018. https://doi.org/10.3386/w24935.

———. “Attitudes towards Debt and Debt Behaviour.” VoxEU.Org (blog), October 27, 2018. https://voxeu.org/article/our-changing-attitudes-towards-household-debt.

“Alternative View: The Dutch Mortgage Market from an International Perspective.” Aegon AM. Accessed September 18, 2019. https://www.aegonassetmanagement.com/global/investment-solutions-center/publications/the-dutch-mortgage-market-from-an-international-perspective/.

“You Have To Understand Germany’s Long-Standing Fear Of Debt.” Business Insider. Accessed September 9, 2019. https://www.businessinsider.com/you-have-to-understand-germanys-long-standing-fear-of-debt-2012-7.

“Average Homeowners Stay 8 Years Before Moving.” Realtor Magazine, May 3, 2019. https://magazine.realtor/daily-news/2019/05/03/average-homeowners-stay-8-years-before-moving.

Badarinza, Cristian, John Y Campbell, Gaurav Kankanhalli, and Tarun Ramadorai. “International Mortgage Markets: Products and Institutions,” n.d., 15.

Bernhardsson, Erik. “Why I Went into the Mortgage Industry.” Erik Bernhardsson, February 17, 2017. https://erikbern.com/2017/02/17/why-i-went-into-the-mortgage-industry.html.

Buckley, Robert M. “Housing Finance in Developing Countries: The Role of Credible Contracts.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 42, no. 2 (1994): 317–32.

Burnett, Victoria. “A Job and No Mortgage for All in a Spanish Town.” The New York Times, May 25, 2009, sec. Europe. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/26/world/europe/26spain.html.

Fabozzi, Frank J., and Franco Modigliani. Mortgage and Mortgage-Backed Securities Markets. Harvard Business School Press Series in Financial Services Management. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press, 1992.

Fernández de Lis, Santiago, Saifeddine Chaibi, Jose Félix Izquierdo, Félix Lores, Ana Rubio, and Jaime Zurita. “Some International Trends in the Regulation of Mortgage Markets: Implications for Spain.” Madrid, Spain: BBVA Research, April 2013. https://www.bbvaresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/mult/WP_1317_tcm348-384510.pdf.

“From Main Street to King Abdullah Financial District: Lessons Learned in International Mortgage Finance.” RiskSpan – Data Made Beautiful (blog), July 12, 2018. https://riskspan.com/news-insight-blog/lessons-learned-in-international-mortgage-finance/.

Green, Richard K, and Susan M Wachter. “The Housing Finance Revolution,” n.d., 47.

Gudell, Svenja. “A Glimpse at Life Without the 30-Year Fixed-Rate Mortgage.” Forbes. Accessed September 9, 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/zillow/2018/03/06/a-glimpse-at-life-without-the-30-year-fixed-rate-mortgage/.

“Here’s How Muslim Buyers Get around the Mortgage Interest Problem—but It’s Tough in NYC.” Brick Underground, February 22, 2017. https://www.brickunderground.com/buy/muslim-friendly-mortgages.

Hobart, Byrne. “The 30-Year Mortgage Is an Intrinsically Toxic Product.” Medium, January 18, 2019. https://medium.com/@byrnehobart/the-30-year-mortgage-is-an-intrinsically-toxic-product-200c901746a.

“Housing Finance Fact or Fiction? FHA Pioneered the 30-Year Fixed Rate Mortgage during the Great Depression?” AEI, June 24, 2015. http://www.aei.org/publication/housing-finance-fact-or-fiction-fha-pioneered-the-30-year-fixed-rate-mortgage-during-the-great-depression/.

“In China, a Three-Digit Score Could Dictate Your Place in Society.” Wired. Accessed September 9, 2019. https://www.wired.com/story/age-of-social-credit/.

Kagan, Julia. “Balloon Mortgage.” Investopedia. Accessed September 23, 2019. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/balloon-mortgage.asp.

McLean, Bethany. “Opinion | Who Wants a 30-Year Mortgage?” The New York Times, January 5, 2011, sec. Opinion. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/06/opinion/06mclean.html.

“Mortgage Loans Around the World.” The Finance Buff, September 29, 2008. https://thefinancebuff.com/mortgage-loans-around-the-world.html.

“New Bubble May Be Building in 30-Year Mortgages.” AEI, December 23, 2011. http://www.aei.org/publication/new-bubble-may-be-building-in-30-year-mortgages/.

Nguyen, Jeremy, Abbas Valadkhani, and Russell Smyth. “Mortgage Product Diversity: Responding to Consumer Demand or Protecting Lender Profit? An Asymmetric Panel Analysis.” Applied Economics 50 (July 21, 2018): 4694–4704. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2018.1459038.

Osborne, Hilary. “Islamic Finance – the Lowdown on Sharia-Compliant Money.” The Guardian, October 29, 2013, sec. Money. https://www.theguardian.com/money/2013/oct/29/islamic-finance-sharia-compliant-money-interest.

Parrott, Jim, Lew Ranieri, Gene Sperling, Mark Zandi, and Barry Zigas. “A More Promising Road to GSE Reform,” n.d., 11.

“(PDF) Mortgage Product Diversity: Responding to Consumer Demand or Protecting Lender Profit? An Asymmetric Panel Analysis.” Accessed September 18, 2019. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323994918_Mortgage_Product_Diversity_Responding_to_Consumer_Demand_or_Protecting_Lender_Profit_An_Asymmetric_Panel_Analysis.

Rodima-Taylor, Daivi, and Parker Shipton. “BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAND MORTGAGE WORKING GROUP RESEARCH REPORT • 03/2017,” n.d., 72.

Rodríguez-Planas, Núria. “Mortgage Finance and Culture.” Journal of Regional Science 58, no. 4 (September 2018): 786–821. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12385.

Scanlon, Kathleen, Jens Lunde, and Christine Whitehead. “Mortgage Product Innovation in Advanced Economies: More Choice, More Risk.” European Journal of Housing Policy 8, no. 2 (June 3, 2008): 109–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616710802037359.

Stoykova, Polina, and Linjie Chou. “Housing Prices and Cultural Values : A Cross-Nation Empirical Analysis,” 2013.

“The 30-Year Fixed Mortgage Should Disappear.” AEI, April 26, 2016. http://www.aei.org/publication/the-30-year-fixed-mortgage-should-disappear/.

“The Challenge of Building Affordable Housing in Developing Countries … and How DFIs Can Help | OPIC : Overseas Private Investment Corporation.” Accessed September 9, 2019. https://www.opic.gov/blog/opic-in-action/the-challenge-of-building-affordable-housing-in-developing-countries-and-how-dfis-can-help.

“The Risky Mortgage Business: The Problem with the 30-Year Fixed-Rate Mortgage.” AEI, December 11, 2012. http://www.aei.org/publication/the-risky-mortgage-business-the-problem-with-the-30-year-fixed-rate-mortgage/.

“What’s So Special about the 30-Year Mortgage?” AEI, February 1, 2011. http://www.aei.org/publication/whats-so-special-about-the-30-year-mortgage/.

“Why Do We Have a 30-Year Mortgage, Anyway?” Marketplace (blog), October 31, 2018. https://www.marketplace.org/2018/10/31/why-do-we-have-30-year-mortgage-anyway/.

“Why the Universal Use of the 30-Year Mortgage Is Dangerous.” AEI, April 22, 2019. http://www.aei.org/publication/why-the-universal-use-of-the-30-year-mortgage-is-dangerous/.