“A Crack in the Foundation?” Part 3: Sideswiped by the American Dream

In the digital age, industries evolve at a breakneck pace, spurred on by technological advents and process enhancements. And yet, as anyone in the mortgage industry knows, change here is less accelerated. We adapt more slowly, seeking respite in the comfort of our well-worn processes and traditions.

The complexity of the mortgage industry necessitates that evolution occurs slowly, and the powers (and policies) that be often set the rate of change. As we look towards the future of our industry, it’s imperative to scrutinize our past to understand the possibilities of our future.

Welcome to “A Crack in the Foundation?”, our four-part series in which we will examine the evolution of the mortgage industry and homeownership in America, with an eye on government policies and how GSEs can promote (or prohibit) periods of economic growth.

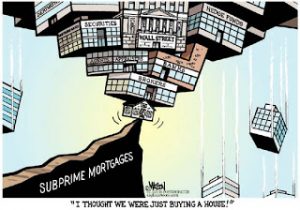

Part 3 starts at the turn of the century and tackles the first decades of the 2000s, including the thorny topic of the financial crisis of 2008 and subsequent recession. Rather than re-tread the well-worn path through the timeline of the subprime mortgage crisis and economic fallout, Part 3 will instead look at the larger question of “why”.

Why did this happen? What signs did we have that this disaster was coming, and why did we overlook them?

Read on to get started.

______________________

The date was September 18th, 2008. Lehman Brothers had just gone under, pulled down by the weight of toxic mortgages. Bear Stearns was long dissolved at this point, and Bank of America had absorbed Merrill Lynch in a spur-of-the-moment sale.Two day prior, President Bush had agreed to an $85B bailout for insurance giant American International Group.

Bush’s Treasury secretary, Henry Paulson Jr., reportedly explained to the President that he would have to sign off on the largest government bail-out plan in history to prevent the country from slipping further into economic ruin.

President Bush paused, for just a beat, stunned by the gravity of the predicament.

Then, he spoke: “How did we get here?”

How, indeed?

Thus far in our winding journey through the history, economics, and policies of the mortgage industry, we have stepped from moment to moment, landing briefly on the cornerstone policies and decisions that shaped the industry over time. We’ve touched on the landmark moments that perhaps happened before our time, or before we entered the industry, to paint a more vivid picture of how we got here.

Part 3, however, brings us into the shadows of recent memory. Just as most of us remember, with stunning clarity, where we were on 9/11, so too do we vividly remember the events leading up to and directly proceeding the subprime mortgage crisis and global financial crash of 2008.

Instead of re-hashing the timeline of what happened (here’s a quick, cheeky recap if you need it), today we are going to focus on the larger questions. How did we get there? Why did it happen?

A word of forewarning: I will not resolutely answer the question of “why” by the end of this piece (nor, I would argue, can anyone answer that question). I will also not assign blame. In truth, we are all culpable.

Certainly, there are undeniable factors at play: investment banks that over-leveraged themselves, borrowers that borrowed more than they needed, lenders who over-looked discrepancies in loan criteria, and regulators that failed to provide proper oversight.

But, even with all that, the crisis could have been averted, says Santa Clara University economics professor Hersh Shefrin, if it weren’t for our psychological biases:

“…overarching all of those pieces is psychology,” Shefrin said. “If it weren’t for psychological issues, even with all of that in place we wouldn’t have the fiasco that we have now.”

Shefrin studies behavioral economics, which incorporates human behavior and psychology into economic theory.

Traditional economic models often have blind spots for hard-to-measure factors like human psychology and people’s expectations about the future.

One cognitive bias that surely played into the crash? The optimism bias. As humans, we tend to take a more optimistic approach than a realistic one when speculating about our future.

In a classic example of this, “psychologist Neil Weinstein asked college students to rate whether they were more or less likely than other students their age to experience 42 various events over their lifetimes. Some events were positive, such as purchasing a house; others were negative, such as getting a divorce; and some were neutral.

Weinstein found that students, on average, thought that they were more likely to experience positive events than other students (that was true for 15 of the 18 positive events), but less likely on average to experience negative events (this was true for 22 of the 24 negative events.)”

“If investment professionals hadn’t been quite so over-confident”, says Shefrin, “then they would have better assessed the risk of holding such huge amounts of their portfolios in mortgage-backed securities, given the risk of being in a bubble. And you would have had less [risky] lending. Homeowners who took out those loans simply wanted the American dream — they bought during a bubble on the assumption that housing prices are going up and will continue to go up.”

And it’s true. No one wanted to question their assumptions, or think about what was around the corner if the housing bubble burst.

Sidney G. Winter, management professor at Wharton, marvels at the incredulity of it all:

“The most remarkable fact is that serious people were willing to commit, both intellectually and financially, to the idea that housing prices would rise indefinitely.”

This reckless optimism fits in with economist Hyman Minsky’s theory that, in periods of prosperity, when corporate cash flow rises above what is needed to pay off debt, a “speculative euphoria” develops, and soon after, debts exceed what borrowers can pay off from their incoming revenues, which causes a financial crisis.

As a result of these speculative borrowing bubbles, banks and lenders tighten credit (even to those who can afford loans), and the economy contracts.

At the center of Minsky’s theory is the idea that financial growth in the period before the crash was driven by excessive ‘Ponzi’-like financing, meaning short-term lending by financial institutions against long-term cash flows that relied heavily on price appreciation.

We wanted to believe that our future was bright, and so we discounted what was in front of us.

We bet on our future, without looking around to see what our present could tell us about what that future might look like.

It’s not the first time we’ve made that mistake.

______________________

“America, from its inception, was speculation,” says historian Aaron M. Sakolski in his 1932 classic, The Great American Land Bubble. Sokolski points out how, during George Washington’s presidency, there was rampant speculation that America would quickly become densely populated, helped in part by vast numbers of immigrants coming to America.

This had investors salivating over rapidly rising land prices. Speculative mania swept across towns, cities, and regions into the 19th century. Prices went up, and continued going up for decades. Until suddenly, they dropped. By 1929, the stagnant market hard reached the stock market, triggering a severe banking crisis that impacted nearly every industry. From 1925 to 1933, home prices fell a total of 30%, and unemployment reached 25%.

Economist Robert Shiller, too, blames this “contagious optimism, seemingly impervious to facts, that often takes hold when prices are rising.

Economist Robert Shiller, too, blames this “contagious optimism, seemingly impervious to facts, that often takes hold when prices are rising.

Bubbles are primarily social phenomena; until we understand and address the psychology that fuels them, they’re going to keep forming.”

According to Shiller, this “boom thinking” fuels speculative bubbles, further encouraged by rising prices. At some point, an economic factor raises prices to a level that warrants optimism, and eventually, enough positive reinforcement convinces us we’ve hit our stride.

In this type of environment, says Shiller, skeptics have a hard time:

“No one has perfect information, and people — quite rationally — infer a great deal from the actions of others. As a bubble expands, some skeptics begin to disregard their own judgement because they feel that everyone else simply couldn’t be wrong.

The recent bubble grew so large partly because the very people responsible for the financial system’s oversight came to share the general public’s rosy expectations. They may not have believed as fervently in the boom, but they still accepted the idea that it would not end badly. Builders kept building, and rating agencies did not temper their sunny assessments of mortgage securities until after the crisis had begun.”

It seems like a cop-out to blame the financial crisis on excessive optimism. It’s like the economic version of saying your biggest weakness is that “you’re kind of a perfectionist” in a job interview.

But, in this case, the culprit really does seem like our unchecked idealism.

The pre-crash era was a dark time. In just a few short years, we were forced to cope with the tragedy of 9/11, the devastation from Hurricane Katrina, and the ongoing turmoil in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Is it that hard to believe that we all — lenders, borrowers, investors, and the like — overlooked the sea of red flags, lured by the comfort and refuge offered by this new, 21st century-iteration of the American Dream?

I think yes. And Shiller does too. But, as he also notes, “unless we apply that understanding to the bubble we’re trying to recover from, we risk calamity.”

Home prices are climbing again, and some economists are predicting a recession is right around the corner. How can we use the insights from our past to proactively protect our future?

_________________

<<< Read Part 2 Read Part 4 >>>