“A Crack in The Foundation?” Part 1: Fannie & Friends — The Evolution of Mortgage Policy from 1930-1969

In the digital age, industries evolve at a breakneck pace, spurred on by technological advents and process enhancements. And yet, as anyone in the mortgage industry knows, change here is less accelerated. We adapt more slowly, seeking respite in the comfort of our well-worn processes and traditions.

The complexity of the mortgage industry necessitates that evolution occurs slowly, and the powers (and policies) that be often set the rate of change. As we look towards the future of our industry, it’s imperative to scrutinize our past to understand the possibilities of our future.

Welcome to “A Crack in the Foundation?”, our four-part series in which we will examine the evolution of the mortgage industry and homeownership in America, with an eye on government policies and how GSEs can promote (or prohibit) periods of economic growth.

Part I starts at the turn of the 20th century and traces the establishment of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), as well as the birth of Fannie and Ginnie, to look at the inception of the modern mortgage and its impact on home ownership.

Read on to get started.

____________________________

The Early Days

In 1781, the first commercial bank was founded in the United States, ushering in a new system of banknotes for exchange with government involvement and minimized liability for bankers, which gave rise to the modern mortgage. By the late 1880s, the mortgage market was in turmoil as a disorganized network of lenders unevenly allocated mortgage loans, with regional favoritism in the Northeast and higher rates in the West.

As of 1905, only four in 10 Americans owned their own homes. In urban cities, renters typically made up nearly 75% of the population.

Before 1916, national banks as well as many state banks were actually prohibited from making real estate loans:

“Even after 1916, many commercial banks refused to make real estate loans on the grounds that they were ‘illiquid.’ Those that were willing to make such loans believed it was ‘bad business’ to lend more than 50 percent of the appraised value of a home. Building and loan associations loaned up to 80 percent or more of the appraised value, but at [higher] interest rates ranging between 8 and 12 percent of the loan.”

The Roaring 1920s were characterized by a laissez-faire economic system featuring a distinct lack of government regulation that spurred rampant speculation and excessive leverage on Wall Street. During the 1928 presidential election, Herbert Hoover promised “a chicken in every pot and a car in every garage.”

Instead, as fate would have it, the stock market crashed in 1929. The banking system collapsed alongside the U.S. financial system as the Great Depression began to ravage the country, with unemployment rates soaring to 25%.

1930s

Before the Great Depression, homeowners experienced variable interest rates, short maturities, and high down payments. They also typically had the ability to renegotiate their mortgages every year. In nearly every state, the law restricted banks and insurance companies to a maximum loan of 50% of the appraised value and limited the loan term to five years (for national banks) or ten years (for insurance companies).

Unsurprisingly, few homebuyers could afford a 50% down payment As a result, most homebuyers took out second and third mortgages at high interest rates. Because the mortgages were relatively short term, they were not amortizing, so at the completion of their mortgage, borrowers would frequently have to obtain a new mortgage to roll over the debt. When home prices plummeted at the start of the Great Depression, first mortgages went into default, followed quickly by second and third mortgages.

As the economy failed, most lenders were unwilling to refinance, and many borrowers could not repay their outstanding debt. In fact, banks called mortgage notes due in an attempt to alleviate their cash crisis.

As a result, one in 10 U.S. mortgages were foreclosed upon, property values took a nosedive, and consumer confidence in bank lending reached a historical low. The losses on those loans directly contributed to the failures of thousands of banks.

As a result, one in 10 U.S. mortgages were foreclosed upon, property values took a nosedive, and consumer confidence in bank lending reached a historical low. The losses on those loans directly contributed to the failures of thousands of banks.

In 1933, the Home Owners’ Loan Act of 1933 established the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) as an emergency agency under the Federal Home Loan Bank Board (FHLBB). The HOLC provided low-interest rate, long-term, fully amortizing mortgages to homeowners unable to procure financing through normal channels. This was the first instance in which the Federal government was established as a mortgage lender, at least for an emergency period of time.

At the end of that year, John H. Fahey, Chairman of the FHLBB, requested an additional $2 billion to fund future HOLC mortgages during a meeting of the National Emergency Council held at the White House.

Upon hearing the request, President Roosevelt reportedly ‘threw up his hands in horror’ and asked ‘if there was a way to get the government out of the lending business.’

As a response to this question, someone present at the meeting suggested that a new housing program might be in order (though Roosevelt would ultimately be disappointed in his desire to extricate the government from the mortgage business).

With the National Housing Act of 1934, the government established the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) as part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal in an attempt to rescue the falling real estate industry and enact changes to mortgage loans to encourage confidence in lending and stimulate the economy.

The FHA played a crucial role in helping pull the country out of the Great Depression; they began to offer mortgages with lower down payments, longer loan terms with amortization, and 80- and 90-percent loan-to-values or higher, aimed at Americans who would not be able to get mortgages under the existing programs.

The FHA established universal standards for qualifying for mortgages and also set quality standards for home construction. Title II of the National Housing Act also permitted the FHA to insure mortgages against the risk of borrower default. In exchange for these benefits, the FHA receives mortgage insurance premiums. This type of insurance is unusual because it involves three parties — the borrower, the lender, and the insurer — rather than two parties, like typical insurance. This encouraged lending by ensuring the lender would be reimbursed by the FHA for virtually all losses in the case of foreclosure.

In an attempt to further stimulate the mortgage market, Congress chartered the Federal National Mortgage Association (today known as Fannie Mae) in 1938 as the first national mortgage association. Though initially limited to FHA loans, Fannie Mae was tasked with expanding the supply of credit beyond depository institutions which both originated mortgages and held them in their portfolio. With Fannie Mae, the mortgage banking industry was created, operating as a new source of mortgage loans in direct competition with savings banks and commercial banks.

The last crucial piece of mortgage legislation in the 1930s was the Steagall National Housing Act of 1938, which effectively dropped the underwriting criteria for FHA-insured single-family mortgages. These changes included increasing the maximum mortgage term from 20 years to 25 years, taking a step closer to the 30-year fixed rate mortgage that would later be established by Congress in the late 1940s.

1940s

The 1940s ushered in an era of consistent growth and prosperity for the mortgage market as home ownership became more accessible to Americans previously excluded from mortgage financing. By 1940, homeownership rates for skilled and unskilled manual workers were not far below homeownership rates for white collar professionals, at nearly 44%. Owning a home was no longer an upper-class affair.

As World War II drew to a close, the VA Home Loan Guaranty Program was authorized by The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 — commonly known as the GI Bill of Rights.

The G.I. Bill was enacted along with the Veteran Affairs (VA) mortgage insurance program, both of which subsidized mortgages for WWII veterans, effectively changing the landscape of the housing industry and American economy:

“The GI Bill’s mortgage subsidies led to an escalated demand for housing and the development of suburbs. One-fifth of all single-family homes built in the 20 years following World War II were financed with help from the GI Bill’s loan guarantee program, symbolizing the emergence of a new middle class.”

Before World War II, it was common for people (especially those in the working class) to buy their first home in their forties when their eldest children had entered the work force and could contribute to the family income. The post-war boom saw more middle-class families purchasing homes earlier in their lives.

But, as economist Daniel K. Fetter argues, the G.I. Bill increased aggregate homeownership rates by shifting the purchase of a home to an earlier stage in life. Fetter estimates that the VA program created by the G.I. Bill can explain roughly 25% of the increase in homeownership rates for those impacted by the post-war loan programs, with homeownership rates for that cohort climbing from 13 to 41%.

In 1948, Congress authorized the 30-year loan term for new construction, and the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage that we know so well was born.

The 30-year mortgage is often said to have been created by the FHA in the 1930s, but this is largely mortgage finance fiction. Congress greenlit the 30-year mortgage for newly constructed homes in 1948 and then later in 1954 for existing homes.

1950s

The 1950s was the first decade in the history of the mortgage market where the true impact of housing policy as a tool for macroeconomic stimulation was felt. As Theda Skocpol notes in “The G.I. Bill and U.S. Social Policy, Past and Future,” approximately one-fifth of post-war mortgages for single-family homes had lower interest rates due to the subsidies and guarantees provided by the VA under the G.I. Bill and successor legislation.

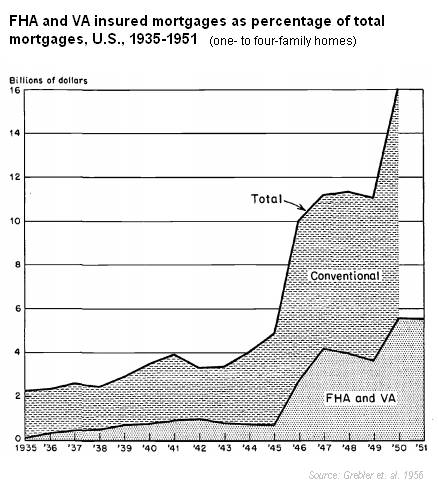

“While these government mortgage programs took a while to have an impact, by 1940, FHA and VA mortgages accounted for 13.5 percent of mortgages, and by 1945 these mortgages accounted for nearly a quarter of mortgages. In 1950 the home mortgage share of FHA and VA mortgages was 41.9 percent. The increased role of these government programs is due to the growth of VA mortgage contracts.”

In many ways, the FHA and the VA redefined what was considered to be a sound, standard mortgage in the 1950s. FHA and VA loan programs helped boost the economy and make the ‘American Dream’ more accessible for millions of Americans. The 1950s saw the most substantial increase in home ownership in American mortgage history. In 1950, there were 8,360,000 more home owners than in 1940, a gain of 55%.

This was in large part due to lower down payments, longer loan terms, and lower interest rates made possible by government-backed programs. The success of the FHA and VA programs also proved that more liberal mortgage terms didn’t necessarily accelerate default rates as expected. This had a ripple effect, prompting private mortgage lenders to loosen their requirements for a mortgage as a reaction to government initiatives that made lending less risky.

Immediately after the war, population in urban areas boomed, creating severe housing shortages, increasing doubling-up, and stimulating new construction. Rural areas, meanwhile, suffered from an oversupply, and dwelling units were lost from the inventory through obsolescence or abandonment as the masses flooded the cities.

In an effort to meet demand, the federal government passed the Housing Act of 1949, which aimed to provide “a decent home and suitable living environment for every American family.”

As a result, the 1950s saw the birth of the suburban neighborhood. From 1944 to 1952, VA backed nearly 2.4 million home loans for World War II veterans, largely concentrated in suburban neighborhoods. As demand for housing rose, so, too did land values, particularly in the suburbs.

In some prime suburban neighborhoods, land values increased by as much as 3,000%, while the population swelled by 45%. Nearly two-thirds of all industrial construction in the suburbs were taking place outside of cities; residential construction in the suburbs accounted for a whopping 75% of all cons truction.

truction.

Economists were at odds during this post-war boom, with many arguing that the benefits of less stringent mortgage terms were offset by skyrocketing home prices as federally subsidized credit was heating up demand for housing, of which supply was already lacking.

There was also some concern about the magnitude of risk shifted from the private to the public sector, particularly as the share of federally subsidized loans on total mortgage debt grew at a breakneck pace, from 10% at the ends of the 1930s to 40% in the 1950s.

For a better understanding of the ballooning amount of federally subsidized mortgage debt, in 1945 (one year after the FHA and VA programs), about $4.1B in FHA-insured loans ($58.2B in 2019) and $200M of VA-guaranteed mortgages ($2.8B in 2019) were issued.

By 1960, those amounts had increased to $26.7B in FHA-insured mortgages ($230.5B in 2019) and $29.7B in VA-guaranteed mortgages ($256.4B in 2019).

1960s

By 1960, the migration from the farm sector had largely run its course and the two homeownership trends — urban and suburban homeownership — substantially merged. Growth in both categories demonstrate that 1940-1960 was a period of unprecedented increase in the homeownership rate — three times the size of decade-over-decade growth before WWII. As inflation pushed taxpayers into higher tax brackets, personal income tax benefits made owning a home preferable to renting. Additionally, substantial growth in income meant that homeownership was possible at an earlier age.

During the 1950s, lenders — led by the example of the FHA — reduced lending standards to make homeownership more successful. In the 1950s, foreclosure rates remained relatively consistent, luring lenders into a false sense of security.

Meanwhile, civil unrest swept the nation in the late 1960s as the Civil Rights Moment gained traction.

In an attempt to alleviate racial discrimination in lending and put a stop to redlining, the federal government enacted Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 (also known as the Fair Housing Act) which sought to eliminate housing discrimination and make home ownership more accessible for minorities.

As Georgette Chapman Phillips, professor of Finance and Economics at Lehigh University, explains:

“[The Fair Housing Act] had two major goals: expand minority housing opportunities, and foster residential integration. Its centerpiece program, Section 235, however, rests in the history books as a failure. Middle-income white families used the program to purchase new suburban housing, while Black families were forced into over-priced, old, inner-city homes of questionable structural integrity.”

The Section 235 program from the FHA was intended to help lower-income Americans who previously could not qualify for mortgages get these new subsidized mortgages with down payments as low as $200 and subsidized, below-market interest rates as low as 1%.

This was great in theory but terrible in practice, as the program unintentionally began to function as reverse redlining:

“Instead of excluding urban black neighborhoods from FHA’s normal mortgages like in the redlining of the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, the 1968 FHA Section 235 program targeted lower-income, urban black neighborhoods for these new, and what turned out to be extremely high-foreclosure FHA mortgages.”

FHA mortgage lending standards began falling in the mid-1950s but bottomed out by the end of the 1960s with the help of Section 235 as foreclosures skyrocketed both inside and outside of the FHA. The low downpayment FHA and VA loans that had seemed so promising suddenly lost their luster:

“During the 1950s, foreclosure rates on VA, FHA and conventional mortgages did not diverge greatly. In the early 1960s, however, rates on VA loans rose appreciably faster than those on conventionals, and rates on FHA’s rose especially rapidly. By 1963, foreclosure rates on VA loans were more than twice as high as estimated rates on conventionals, and rates on FHA loans were roughly four times as high.”

Trouble had been brewing since the early 1960s but warning signs were largely ignored, and FHA borrowers paid the price:

“From 1977 to 2013, one in eight FHA borrowers lost their homes to foreclosure — well over 3 million families. This was 60 times the FHA claim rate from 1934 to 1954, as result of the major liberalization in terms for FHA insured mortgages which were enacted by a series of amendments to the National Housing Act from 1954 onward.”

As the mortgage market suffered, President Johnson was eager to figure out how to privatize Fannie Mae in order to remove Fannie Mae’s debt from the federal government’s books, thereby reducing the size of the national debt.

As part of the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968, Fannie Mae was split in two. One half became new Fannie Mae, which was converted from a federal government entity to a stand-alone government sponsored enterprise (GSE) to purchase and securitize mortgages to facilitate liquidity in the primary market. Fannie Mae became a publicly traded company on the New York Stock Exchange, but with an added honor: Fannie Mae would be granted five board members to their board of directors that were hand-picked by the President of the United States.

The other half became Ginnie Mae, which remained a government agency under the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Like its cousin Fannie, Ginnie Mae was established to increase the amount of capital available in the primary market for lenders to offer government-backed mortgages. Unlike Fannie, Ginnie Mae does not purchase or securitize mortgages; rather, it guarantees mortgage-backed securities issued by certain issuers (like banks or credit unions) that have been approved by Ginnie Mae.

Conclusion

The Federal Housing Administration is often credited for the spike in homeownership from 1940-1960, with many claiming that it was the FHA’s creation of the low-down payment, 30-year, self-amortizing mortgage that largely helped raise the home ownership rate from 44% at the end of the Great Depression to 62% in 1960. However, it’s worth noting the 30-year fixed-rate loan was not even authorized by Congress for new construction until 1948, and for existing homes in 1954.

Furthermore, that view completely overlooks Fannie Mae’s rapidly growing influence in the market. The booming national mortgage market in the 1950s and 1960s was heavily influenced by the growing secondary mortgage market, and the government continued to intervene in the secondary market by adjusting Fannie Mae’s market involvement.

As economist Katharina Gärtner notes:

“These special functions continued the trend of using intervention in the mortgage market as a form of social-assistance policy. Most of these instruments represent indirect and off-budget support for mortgage lending rather than, say, direct subsidies for the construction of housing.

Overall, these government activities had a marked influence on the behavior of all three groups participating in the housing market: debtors, investors, and builders. These individual instruments effectively led to emergence of a permanent system for the subsidization of residential mortgage credit. The long institutional history of these programs underscores the far-reaching effects of Depression-era legislative action.”

In other words, mortgage policy in the New Deal era set the stage for the policies that would come in the decades to follow — for better or for worse.

As the national mortgage market expanded and grew its influence in the U.S. economy, the powers that be quickly realized that short-term policies to boost mortgage lending could have a ripple effect in the larger economy. But, as we will quickly see in Part 2 (and Part 3…), these quick fixes and short-term gains often resulted in bigger problems in the long run.

____________________________

Read Part 2 (1970-1999) >>>